Some call this prison the Alcatraz of Argentina. Its inmates helped build what’s now known as the city at the end of the world.

Sent here in the early 1900s to populate the country’s southern tip, they paved the roads and heated homes with timber they hauled by train from nearby forests. Ushuaia’s frigid climate and remote location meant that if inmates managed to escape the prison grounds, they rarely got far.

Nestled along the Beagle Channel with snow-capped mountains behind it, Ushuaia grew into a significant port city of 80,000 and a hub for ecotourism. Ships depart regularly for Antarctica.

The prison has been turned into a museum and “dark tourism” attraction — like Chernobyl — that serves as a reminder that Ushuaia owes its existence largely to the labor of the inmates.

Gift shops tout a seemingly endless supply of prison-themed souvenirs, among them baby onesies and oven mitts in the signature design of prison uniforms — yellow and blue horizontal stripes. The End of the World Train that traverses the Tierra del Fuego National Park simulates the forest journey that prisoners made daily and invites passengers to experience “the charm of an era that has passed.”

The kitschiness fuels a debate about whether commodifying “dark tourism” is distasteful or makes history more accessible. Ryan C. Edwards, author of “A Carceral Ecology,” which examines the Ushuaia prison and its legacy, said people should not forget Ushuaia‘s past.

“It’s very funny to ride the train, hear the stories, be somber about it and then be happy when you’re trekking through the mountains,” he said.

But Ushuaia’s history as a city and a prison poses an uneasy question.

“The one is because of the other,” Edwards said, “and are we OK with that?”

The Tierra del Fuego city, which bills itself as the End of the World, cashes in as thousands flock to its relatively untouched terrain.

When Argentina established a subprefecture in Tierra del Fuego in 1884, following a treaty with Chile that divided the territory between both countries, the region was populated by Indigenous people and English missionaries.

Argentine officials, including President Julio Roca, saw a prison as a way to obtain a reliable source of hands and occupy the territory to defend it from Chile. They pointed to penal colonies around the world, including Britain’s settlement in Australia, as models.

The name Ushuaia, pronounced oo-SWY-yah, comes from the Indigenous Yaghan language and means “the bay that looks west.”

A group of prisoners who were promised reduced sentences volunteered to transfer to Ushuaia to build a jail for civilians, according to Edwards. In 1902, the founding stone was laid in sight of the shores of the Beagle Channel.

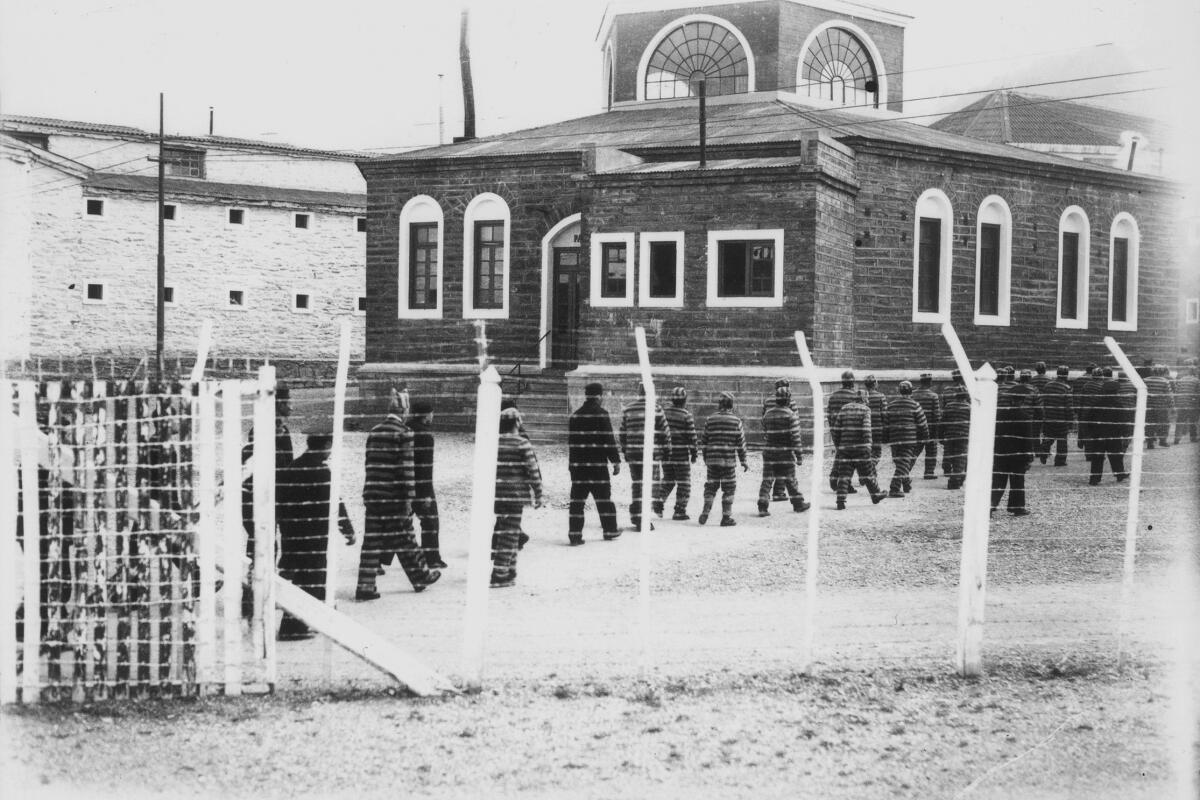

1

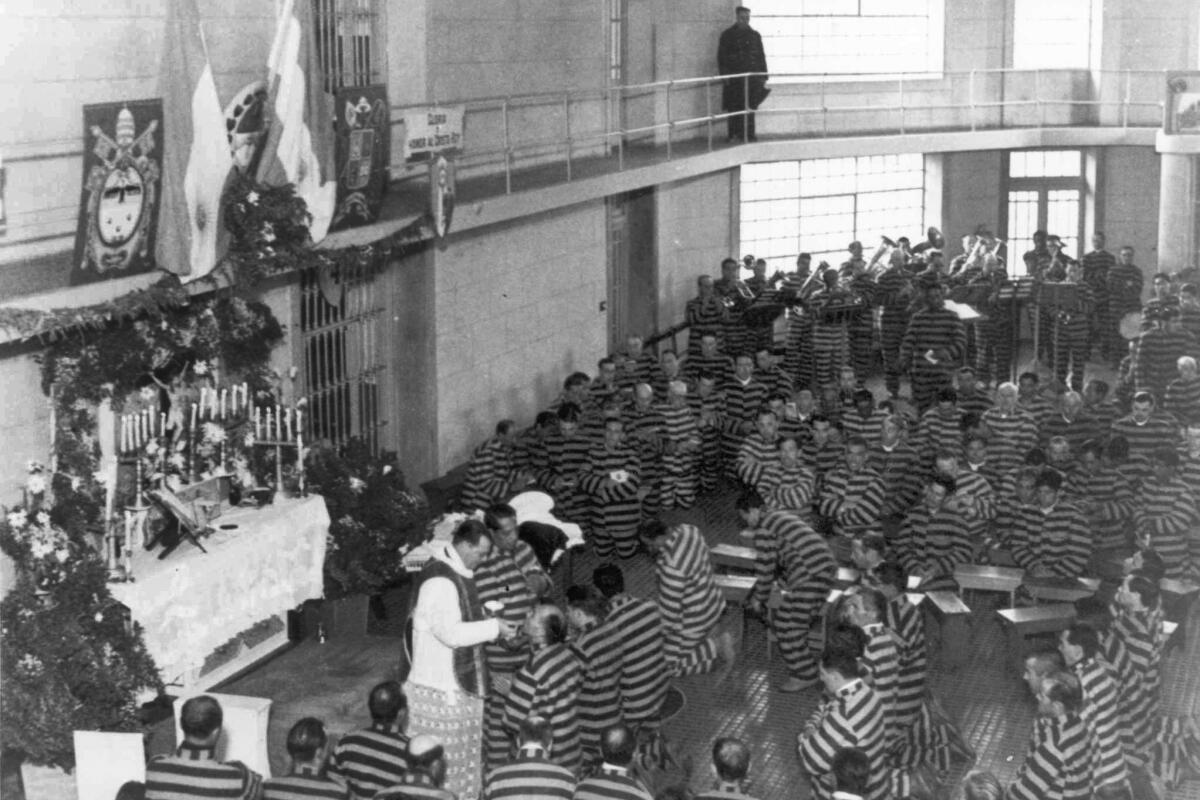

2

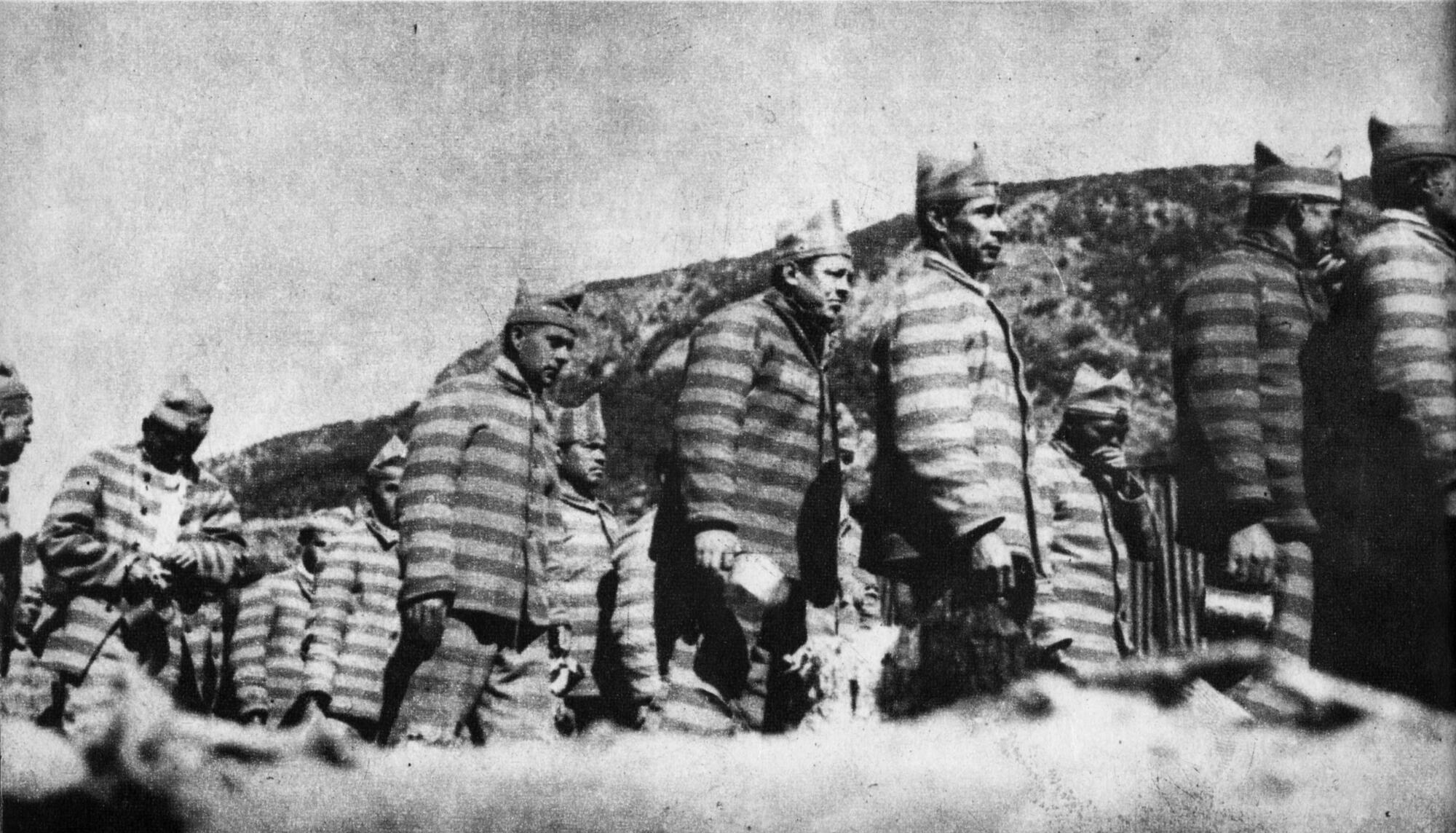

3

1. Successful prison breaks were rare in Ushuaia because of its frigid weather and remote location. 2. Inside the prison’s rotunda. Prisoners often lived in crowded conditions. 3. An outside view of Ushuaia’s prison. (Courtesy Museo del Fin del Mundo - Ushuaia)

The prison’s design, five long cellblocks that meet at a rotunda like spokes of a wheel, was inspired by the famous Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. Some proponents thought that physical labor and Patagonia’s nature and cold climate could help rehabilitate the prisoners.

“There’s a belief that cold frigid zones will actually temper criminal habits,” said Edwards. “You get a very scientific penitentiary in a very cold region that they believe to be salubrious.”

The penitentiary grew to 380 cells while housing more than 500 prisoners at a time, and suffered from overcrowding. The prison had a bakery, mechanic, tailor shop, newspaper and sawmill, and prisoners handled the city’s construction projects. It also ran a plant that generated electricity for the town, which experienced blackouts when the prison, under the jurisdiction of the country’s Ministry of Justice, cut off electricity during conflicts with local officials.

“The town became completely dependent on the jail,” said Silvana Mabel Cecarelli, an Argentine historian who has written several books on the prison. “They wanted a crib, they had to buy it from the prisoners.”

Prisoners who escaped weren’t expected to survive. Some made it to the wilderness only to start fires in hopes of being spotted and rescued.

The prison held famous criminals, including serial killer Cayetano Santos Godino, who was charged as a teenager with strangling children. At a time when biological traits were studied as indicators of criminal behavior, Godino became known by the public for his large ears and nicknamed the petiso orejudo, “the short large-eared man.”

The case of Simón Radowitzky, an anarchist who was transferred to Ushuaia in 1911 after assassinating the Buenos Aires police chief in the aftermath of violent clashes between police and labor movement protesters, put a media spotlight on the prison and fostered demands for its closure.

Journalists who visited wrote about disease and lack of heating. One reporter from a Buenos Aires newspaper who secretly interviewed prisoners as they worked outside wrote that “Ushuaia, the cursed land, is a disgusting stain on the Republic.”

“It was like leaving them forgotten,” said Cecarelli. “The area got a reputation as a place of punishment; that’s why it was called the ‘Siberia Criolla,’” the Argentine Siberia.

As the number of prisoners and prison employees grew, Tierra del Fuego’s population increased from 477 in 1895 to 2,504 in 1914.

Ushuaia’s families adapted to the environment, warming their beds with heated bricks and spending their free time ice skating in the street, climbing a nearby glacier and trekking in the forest. News from Buenos Aires and the rest of the world arrived by radio, and canned food and supplies arrived on cargo ships in the port.

Mar Tita Garea, 84, a resident of Ushuaia and known as one of its “old settlers,” recalled how her father, who worked in the prison’s tailor shop when she was a child, would bring home fresh bread from the prison’s bakery every day.

“It was tasty, even tastier than what my mother would make,” she said.

Garea would occasionally hear the prison’s orchestra, which would perform for the public on national holidays, but worried when news that a prisoner had escaped would sweep the town.

“People would get scared, or at least I got scared,” she said.

Another resident, Rúben Mu?oz, 85, whose uncle was a prison guard, remembered gathering every evening with other children in town to watch as the train carrying prisoners back from collecting timber passed by a main street.

“There wasn’t television, there weren’t movies, so it was a kind of entertainment,” he said.

In 1947, President Juan Perón announced the closure of the prison in the wake of national reforms that created labor-oriented rural prisons throughout Argentina in order to support the development of agricultural communities.

Argentina’s President-elect Javier Milei has shown public interest in Judaism, incorporating shofars at campaign rallies and visiting a rabbi’s tomb.

Ushuaia, even without its prison, kept steadily growing. In the ’70s, tourism to Antarctica, a two-day boat ride away, boomed. Tax exemptions created in Tierra del Fuego to lure people to the province led to the development of a manufacturing hub that today produces almost all cell phones and television sets in Argentina.

These days, tourism is one of the city’s lifelines. In the summer, visitors pack the downtown’s narrow streets where agencies offer excursions to see penguins and last-minute trips to Antarctica and souvenir shops sell mugs and shirts that say “end of the world.”

Before boarding the End of the World Train, passengers take photos next to staff dressed in horizontal stripes to impersonate prisoners. A recording tells the story of the prison in multiple languages while the train passes by a glistening river and valleys. The venture has been a success. Last year, the train had 259,000 passengers, up from 102,000 in 2013. A decade earlier, it had 60,000.

A mannequin of a guard in uniform greets visitors at the entrance of the prison, which in the ‘90s was converted by a group of locals into a museum. Repainted cells host exhibits, and two cellblocks house an art gallery and gift shop.

Tourists take pictures with a prisoner figurine sitting at a cafe table inside the rotunda. Rolando Bianco, a Buenos Aires businessman, posed for a photo with a diploma from the gift shop that declares visitors “free.”

“Something humorous,” he said. “You have to take life like that.”

Many locals are happy with the boost to the economy. Ana María Calderon, whose father was an orphan in Buenos Aires and had never heard of Ushuaia when a church found him a job there at age 20 helping print a newspaper, said that when she grew up the town felt very subdued.

“Seeing the people, the ships, it gives me life,” she said.

But José Enrique Cisterna, a 95-year-old who moved to Ushuaia at 18 and worked on the naval base that took over the prison, said that it’s important to remember that “the suffering of the prisoners helped expand the city.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.