‘We have to go to war’: The man battling Disney’s Bob Iger — and increasingly long odds

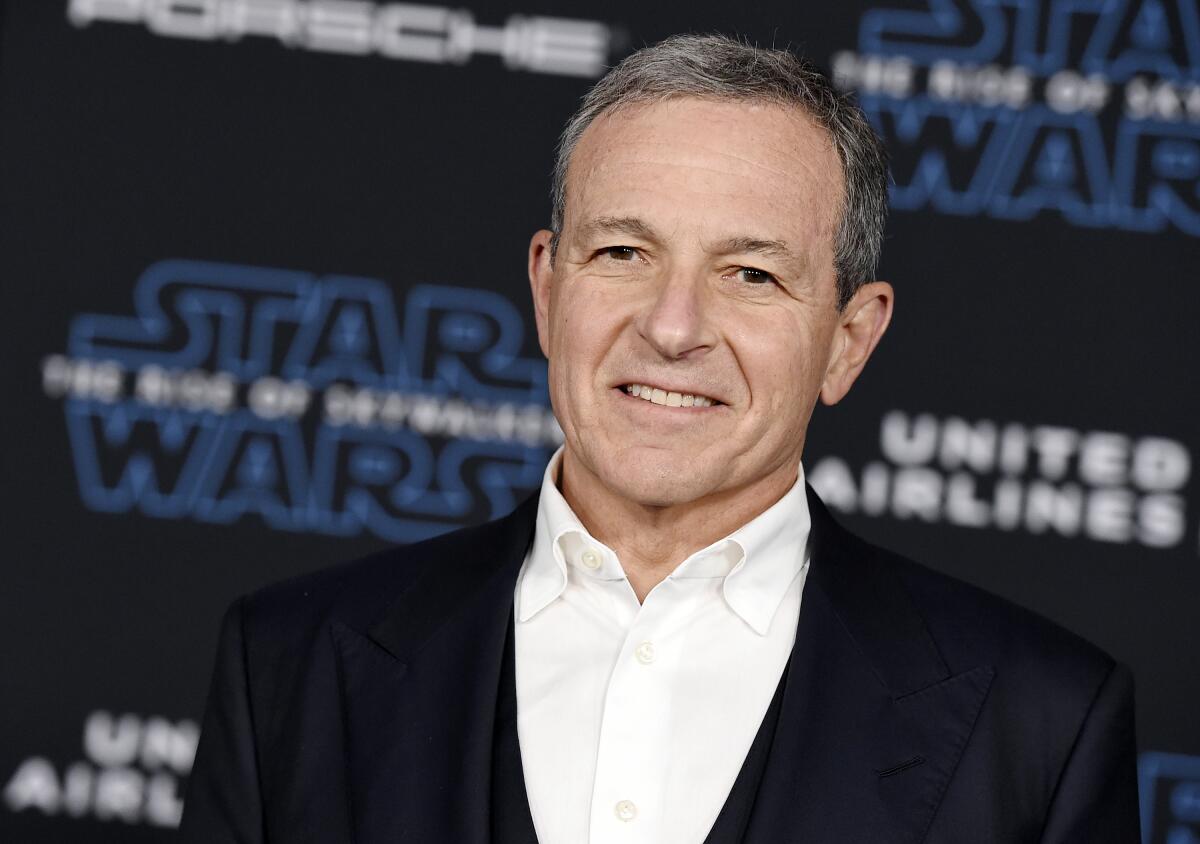

This month, after Walt Disney Co. reported stronger-than-expected earnings, it appeared that the promise of Bob Iger’s return as chief executive might finally be on track to put the magic back into the kingdom.

After a year that saw the entertainment giant buffeted by Hollywood strikes, major layoffs and stock price stumbles, the earnings report (and several headline-making announcements) sent Disney’s shares soaring, achieving the stock’s best day on Wall Street in three years.

The strong showing also appeared to deflate activist investor Nelson Peltz’s efforts to mount a boardroom shakeup at Disney’s upcoming annual shareholder meeting in April.

Just months ago, it looked as though Disney CEO Bob Iger was struggling in his return to the legendary Burbank company. Now, he is on offense again as the company faces two boardroom challenges.

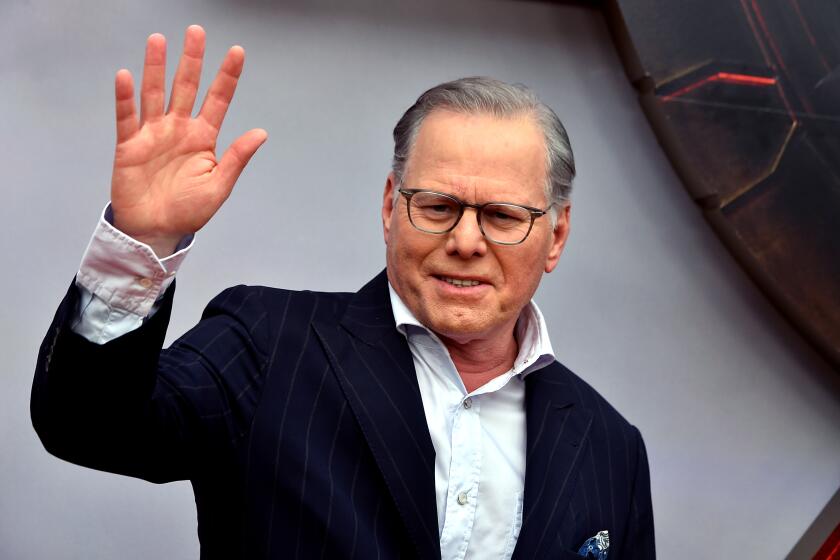

But Peltz, 81, who was once described as having “a piratical charm and a velvet glove,” refused to back down. Within days, the pugilistic investor was throwing shade on Iger and Disney’s board, and criticizing their plans to move the company forward, vowing to continue his proxy fight against Disney — his second in less than a year.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“These pronouncements, this reminds me of a politician making election day announcements versus State of the Union speeches. State of the Union is what I want to hear about, not election day promises,” he said, during an appearance on CNBC’s “Money Movers.”

For those who know Peltz, the CEO and founding partner of Trian Partners, this was more than just showmanship.

The billionaire investor has a history of waging vitriolic battles with major companies. As he has said, “If we can’t agree on the problem, we have to go to war.” His strategy of demanding board seats and implementing change has generated a raft of big wins.

But with Iger having regained trust with many shareholders, Peltz’s bet on Disney is looking increasingly risky. Whether his fight with the Mouse House will end in a spellbinding triumph or an embarrassing failure, Peltz has dug in. He now holds a weakened hand, and this could end up being one of his rare misfires.

Investors and activists have been unusually blunt about Peltz’s proxy fight, calling it quixotic.

“I see no indication of widespread shareholder support for what he’s doing,” said Nell Minow, a shareholder rights activist and vice chair of ValueEdge Advisors. “The first thing you have to do is you’ve got to find a target that everybody’s mad at, and you just don’t have enough people that are mad at Disney.”

Peltz, through his representatives, declined to comment.

A spokesperson for Disney declined to comment beyond the company’s proxy statement.

A different kind of corporate activist

Peltz is among a powerful cadre of activist shareholders — a class that includes Carl Icahn, Bill Ackman, Dan Loeb and Paul Singer — who have forced companies to change through public challenges, backed up by sizable stakes in them. While these fights have become something like an elegant cage match, they have also become a fundamental part of the corporate landscape, changing the ways in which boards interact with shareholders.

Last year, activists launched 183 campaigns, up 21% from the previous year, according to the Lazard Annual Review of Shareholder Activists. In North America, they won 88 board seats through proxy fights.

Peltz eschews the moniker “activist investor” and, unlike some of his cohorts, he tends to nominate himself for a board seat. He’s known for taking long-term positions, working to revitalize companies rather than leverage them up or sell them for parts.

“People talk about him as a corporate raider. He’s not a corporate raider like Carl Icahn,” said Los Angeles investor and deal-maker Lloyd Greif. “I think he’s much more experienced in running companies. A lot of these guys were financial engineers, and they would come into a company and immediately look at, how do we break this company up to maximize value.”

With a helmet of white hair and nattily dressed, Peltz retains traces of his Brooklyn childhood, chiefly his accent, but also his forthright, pull-no-punches style.

In 1962, bored, he dropped out of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and headed to Maine to be a ski bum.

However, when the snow melted in the spring, he returned home to work as a truck driver at his family’s business, A. Peltz & Sons, a wholesale produce distribution business founded by his grandfather in 1896 that expanded into frozen foods. Nelson Peltz earned $100 a week. His plan was to save enough for gas money to move to Oregon to teach summer race camp.

Peltz never made it.

Working for the business, he noticed numerous missed opportunities and mistakes. When he mentioned his observations to his father, the elder Peltz responded, ”Why don’t you stay for a year and address them?” he told students at the University of Miami business school.

Over the next 15 years, the younger Peltz grew the business. He acquired other companies, built a sales force and brought in his older brother Robert and a business partner, Peter May.

The company, now called Flagstaff Food Service, went from annual sales of $2 million to $150 million and became the largest food distributor in the Northeast. In 1971 the company went public; it was sold eight years later.

While Peltz was building up his family business, he also began a small investment fund, using the money he earned from his bar mitzvah and funds from family and friends.

By the 1980s, Peltz amassed a multimillion-dollar fortune through a number of leveraged buyouts financed by junk bonds sold by Michael Milken.

In 1983, along with his partner May, Peltz bought a stake in Triangle Industries, becoming its CEO and making it the world’s largest packaging company. He sold it five years later for nearly $1 billion to French conglomerate Pechiney, S.A.

Peltz’s early successes led to a string of even bigger and more audacious wins.

His most celebrated deal was the $300-million acquisition of the flailing iced tea brand Snapple from Quaker in 1997. Within three years, he brought back its fizzy appeal and sold it for more than $1 billion to Cadbury Schweppes. The deal became the subject of a Harvard Business School case study and earned Peltz a reputation as one of America’s princely turnaround kings.

In 2005, he founded Trian Fund Management, an alternative investment management fund, with May and Edward Garden, his son-in-law. Trian bought up significant stock positions in companies such as Heinz, Wendy’s and DuPont and demanded board seats and proposed significant changes, often clashing with their CEOs.

“I like fixing things and I like growing things,” Peltz once explained to Bloomberg Wealth, adding, “We wouldn’t be there if they were really doing well.”

Peltz became known as an “operational activist” who wasn’t afraid to take on large-cap publicly-traded corporations, and he wasn’t one to back away from a fight. He had an intense persistence and attention to detail, and often became a lightning rod, if not an unwelcome change agent, for the companies in his sights.

When Peltz took on the H.J. Heinz Co. in 2006, the corporation rebuffed Peltz’s turnaround plan. He “doesn’t understand our business,” its chief executive, William Johnson, told the New York Times, and cautioned that if he got “on the board, you’re going to have a destabilizing situation.”

Peltz prevailed, winning a pair of board seats, and Johnson did an about-face, later saying, “He was very informed, highly-focused and an engaged director.”

Over the next seven years, Heinz’s stock price increased 61%. In 2013 the company was acquired by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital in a deal valued at $28 billion; two years later it merged with Kraft Foods.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Peltz later was invited to join the board of Mondelēz International, a global snack business.

“He provoked management and pushed the other directors to ask hard questions,” said Mondelēz CEO Dirk Van de Put. “You might not like it, but overall it was good for the well-being of the company.”

Today, Trian has $8.5 billion in assets under management and Peltz’s net worth is estimated to be $1.5 billion, according to Forbes.

Outside of the boardroom, Peltz lives large.

He married his third wife, former model Claudia (née Heffner), in 1985. They have eight children in addition to the two he had with his first wife.

The couple split their time between two mega-mansions: Montsorrel, a sprawling waterfront estate in Palm Beach, Fla.; and High Winds, set on 130 acres in Bedford, N.Y., from which Peltz once commuted to his Manhattan office in a Sikorsky helicopter. But his neighbors complained about the noise and the town took him to court. It was a rare defeat for Peltz, who lost the five-year legal fight.

Until last year, Peltz’s battles were largely relegated to the financial press. Then, he sued the Florida wedding planners who were hired to handle the nuptials of his daughter Nicola, an actor who married Brooklyn Beckham, the son of British footballer David Beckham and his wife, former Spice Girl and fashion designer Victoria Beckham, in April 2022.

In legal filings, Peltz said he fired the planners after they failed to deliver on their contractual obligations and did not return his $159,000 deposit. He said the planners “hoodwinked” him and he accused them of “falsely portray[ing] Nicola in an extremely negative light to entice the media.”

Before the parties eventually settled, the wedding planners filed a 181-page countersuit for breach of contract, calling Peltz a “bully billionaire” and making him a target of the tabloid press.

A risky Disney fight?

Peltz launched his first proxy campaign against Disney in January 2023, after an unsuccessful attempt to gain a board seat the previous year. The company’s share price was languishing and by September it hit an eight-year low, falling below $80. Trian owned about 9.4 million shares worth some $900 million; that number later swelled to 32 million shares valued at $3.6 billion.

Peltz was unsparing in his criticism: calling out Disney’s “over-the top” compensation practices, failure to implement a succession plan (in July, the board extended Iger’s contract for two more years until 2026) and weak corporate governance.

He highlighted “self-inflicted” wounds such as the $71.3-billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019, a string of box-office bombs, as well as the entertainment giant’s money-losing streaming business.

“Disney’s recent performance reflects the hard truth that it is a company in crisis,” said Trian in an excoriating statement.

In February, when the company announced plans to eliminate 7,000 jobs, slash $5.5 billion from its budget and restore dividends, Peltz dropped his demands.

With characteristic hubris, he declared his proxy war was over and took a victory lap. “If a guy is going to do everything you wanted him to do, where’s the argument?” he told Fortune.

During the following months, however, as Disney’s stock price stalled, so did Trian’s confidence in the company’s ability to get on the right path.

Last fall, Peltz fired off his latest proxy salvo — this time agitating for multiple board seats, one for himself and another for Jay Rasulo, a former Disney chief financial officer.

“It’s déjà vu all over again,” Trian said in a statement. “We saw this movie last year, and we didn’t like the ending.”

For years, Peltz’s shareholder activism was restricted mostly to shaking up the boardrooms of American corporations, with big consumer brands like Wendy’s, Heinz and DuPont that sold tangible products like hamburgers, ketchup and chemicals, not dreams.

His detractors say Peltz’s war with Disney is misguided.

“I don’t think that anything in his track record indicates that he can come up with a good strategy for this particular company,” said Minow. “He’s an expert in balance sheets, but I don’t know that in a company like Disney that’s what you need.”

“He’s offered no ideas for the Disney strategic situation because he has no ideas and he has no background in media,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, founder of Yale’s Chief Executive Leadership Institute. “He’s an industrial consumer-goods guy with no media, technology or media marketing background.”

It is much the same argument that Disney itself has made in its rebuffs of Peltz.

Peltz “had not actually presented a single strategic idea,” said the company in a letter to shareholders, noting that his background in consumer goods did not align with “a business that is primarily driven by creative talent and focused on delivering uniquely memorable customer experiences.”

But Peltz has countered, at least in broad strokes, that the company is under-performing and that he wants to work with the board and management to set ambitious but achievable targets to improve corporate governance, streaming, ESPN and the movie studios, creativity and the parks and experiences.

“Nelson knows brands and Disney is ultimately a company of brands,” said someone familiar with Trian who was not authorized to comment publicly. “And Jay [Rasulo] spent three decades there in a variety of roles. He was CFO during a time when stock price increased by more than 250%, and the company paid more than $8 billion in dividends.”

In the coming weeks, Trian is expected to make public its “white paper,” the firm’s detailed analysis outlining Peltz’s case for Disney.

In the meantime, Peltz has found support in other influential quarters.

Trian’s website has a page showcasing the testimonials of 11 CEOs of companies the firm has invested in and/or engaged in proxy fights with, including those of Procter & Gamble and DuPont.

Last October, former Marvel Entertainment Chairman Isaac “Ike’’ Perlmutter joined forces with Peltz, entrusting his Disney shares to Trian (hence the massive bump to 32 million shares last fall). Perlmutter was dismissed from his role at Marvel last March as part of a larger restructuring. Disney has claimed that the former Marvel executive has a personal agenda against Iger.

Perlmutter did not respond to requests for comment.

More recently, Peltz’s efforts were buttressed by Elon Musk, another bête noire of Disney.

In January, Musk, who has bitterly criticized Disney for pulling its advertising from his social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, wrote on the site: “Brutal track record. Shareholders have been incredibly poorly served by the @Disney board!”

The following month, Musk appeared on the red carpet with Peltz in Los Angeles for the film premiere of “Lola,” the directorial debut of Peltz’s daughter, Nicola Peltz Beckham, who also stars in the film. Musk then kicked his own feud with Disney up a notch, offering to help pay legal fees for those suing the company for discrimination.

With the April shareholder meeting fast approaching, things are getting heated.

In February, a group representing Blackwells Capital tweeted out part of Wendy’s 2023 proxy statement that showed Peltz, a board member, billed the company nearly $600,000 for his personal security, writing: “Who knew that hamburgers could be so dangerous! Is this how Peltz plans to perform for @Disney 蝉丑补谤别丑辞濒诲别谤蝉?”

Peltz, however, remains resolute and unmoved. On Valentine’s Day his firm sent shareholders a new fight letter. It was illustrated with an unflattering cartoon of Disney’s board throwing spaghetti at a wall.

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.