The crowd applauded the moment Kevin de León walked up.

Abuelas pulled him in for a warm embrace. Entire families, standing in line at the recent El Sereno food giveaway, asked for selfies with him.

In this place, no one called him racist, or a disgrace, or 蝉颈苍惫别谤驳ü别苍锄补 — someone without shame — for ignoring calls to step down in the wake of a scandal that drew nationwide condemnation. Instead, the Los Angeles City Council member beamed as he made his way down a line of more than a hundred people, shaking hands and greeting them in Spanish and Cantonese.

One woman declared him “el mero mero” — the top dog.

Another, 71-year-old Guadalupe Casta?eda, yelled from her spot in line: “We’ll help you campaign!”

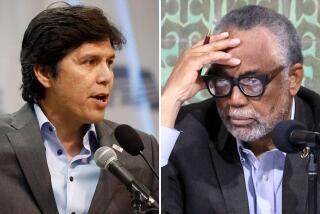

For nearly a year, the 56-year-old De León has clawed his way back from political purgatory, unveiling new street signs, showing up at awards dinners and chatting with constituents at his food giveaways. Although he lost all of his committee assignments, he is back on the council floor, casting votes and occasionally giving speeches.

And despite weeks of protests outside his Eagle Rock home, a physical fight with an activist and a call by President Biden to step down, he is doing what many thought would be an impossible task: waging an uphill battle for reelection.

But in recent days, there have been questions about the depths of his remorse — and limits to the city’s willingness to forgive.

Some council members won’t stand next to him, as if worried his very presence might sully them. Labor leaders who once supported him have turned their backs. Friendships have ended. Allies are now outright foes.

De León, who has served in both houses of the state Legislature, became a political pariah in October 2022 when he was heard participating in a secretly recorded conversation that featured racist and derogatory remarks targeting Black people, the city’s Oaxacan residents and a number of elected officials.

At no point did De León rebut those remarks, or put a stop to the conversation. Instead, he took part in several of the most incendiary exchanges, including one in which then-Council President Nury Martinez accused Mike Bonin, a white council member who is gay, of using his young Black son as an accessory akin to a designer handbag.

De León, in an interview at his Eagle Rock office, told The Times he should have “shut that meeting down,” putting a halt to the invective, or steering it toward other topics. He described some of his remarks on the audio as “inartful,” saying they should have been phrased differently.

He said he has asked hundreds of people for forgiveness over the past year, reaching out to elected officials, neighborhood organizers and religious leaders, including members of the Black clergy. He said repeatedly that he has owned his mistakes.

“When you make a mistake, you have to eat shit,” he said. “And that’s what I’ve been doing.”

De León struck a far more defiant tone in a recent lawsuit targeting two people who worked in the building where the audio was secretly recorded. That filing, which can be viewed on the court’s website but has not been fully processed by the Superior Court system, said De León “never made any comment that was even remotely offensive.” The legal filing also blasts the news media over its coverage of the scandal, saying outlets were “more concerned with clickbait than facts.”

“His critics continue to engage in guilt by association for comments that were not his,” the document said.

With the election five months away, De León is betting that voters will give him another chance. He hopes they will recognize his work creating parkland, adding homeless beds, advocating for new tenant protections and distributing food to the city’s neediest.

De León’s critics are pushing back, saying he hasn’t taken the necessary steps to warrant forgiveness. The way for him to atone, many of them say, is to abandon his campaign and step down from his office.

“I think he is trying to reinvent himself,” said state Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles), who is running for council and looking to oust De León. “And in many ways, it feels like he is gaslighting the entire district and the entire city, by thinking that we’ve all forgotten … what was said in those leaked audio recordings.”

Jasmyne Cannick, a political consultant and longtime critic of De León, was equally skeptical.

“I don’t think this mistake is unforgivable,” Cannick said last month. “I just think he hasn’t done the work yet to be forgiven.”

::

In October 2021, De León, Martinez and Councilmember Gil Cedillo walked into the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor headquarters to speak with Ron Herrera, then head of the organization. They were there for the kind of meeting that, under normal circumstances, few would have known about.

What they didn’t know was that someone was secretly recording it. (The LAPD has opened an investigation into the source of the audio.)

The recording captured an hourlong conversation among De León and the other three. They were there to discuss the city’s contentious redistricting process — and how to push back against a citizens’ commission proposal for redrawing the maps of each of the council’s 15 districts. But the conversation veered into more disturbing subject matter.

The clandestine recording was a ticking time bomb. It exploded when its contents were posted on Reddit.

A leaked recording of L.A. City Council members and a labor official includes racist remarks. Council President Nury Martinez apologizes; Councilmember Kevin de León expresses regret.

On the audio, Martinez used a profanity to describe Dist. Atty. George Gascón and said he’s “with the Blacks.” At another point, she referred to Oaxacans as “little short dark people.” De León took aim at the state’s white politicians, warning his Latino colleagues that they will “cut you in a heartbeat.”

Much of the animus was trained on Bonin. On the audio, Martinez said twice that Bonin “thinks he’s Black.” She complained about the behavior of Bonin’s Black son at a parade, saying the child deserved a “beatdown.” At one point, Martinez used the word changuito — little monkey — to describe the young boy.

When Bonin heard what was on the recording, he said he felt a rush of emotions: anger, frustration, disgust. In an interview with The Times, Bonin stressed that De León “was not a bystander” to the recorded conversation but an active participant who twice reminded Martinez that his son is Black.

“Kevin is the one who brought my son into the conversation,” Bonin said. “It galls me that that gets forgotten, because he’s rewriting the history of what happened on those tapes.”

The contents of the recording instantly reframed the public’s perception of De León, who had impressed many progressive Democrats for his advocacy on immigrant rights, his embrace of measures to combat climate change and his long-shot 2018 campaign against U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who had been derided as too moderate.

Protesters flooded into the council chamber, bringing meetings to a halt. Politicians, community leaders and many others called for everyone involved in the recorded meeting to resign.

Herrera was the first to step down, then Martinez. By the time the audio leak happened, Cedillo had already lost his reelection bid. Instead of stepping aside, he simply disappeared from public view.

De León, the last one standing, took a sharply different approach. He made the media rounds, sitting down with talk radio host Tavis Smiley, using his show to apologize and ask the Black community for forgiveness.

His remarks did little to stem the outrage.

For 18 days, activists camped out near the councilman’s home, wearing shirts with the message “25 Black People Yelling.” That was their response to De León’s claim on the audio that L.A.’s Black community, despite being much smaller in numbers than the Latino population, has outsized political power.

Twenty-five Black residents “shout like they’re 250,” De León had said. “When there’s 100 of us … it sounds like it’s 10 of us.”

De León went so far on the audio as to compare Black political clout to the man behind the curtain in “The Wizard of Oz,” who projects a booming voice but is revealed to be a soft-spoken figure.

Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles, said she found those remarks to be among the most troubling.

“We decided that we were going to show him what 25 Black people yelling sounded like,” said Abdullah, who estimated that on one night, the crowd near De León’s home reached 700.

When the encampment dispersed, activists set up a tip line to track De León’s whereabouts. That led to protests at a private club and a restaurant, Abdullah said. When the councilman’s office began announcing constituent events, activists made sure to be there.

In December, protesters chased after De León and his staff at a holiday toy giveaway in Lincoln Heights. De León and activist Jason Reedy wound up in a physical altercation, with each man accusing the other of committing assault. Neither was charged.

Weeks later, Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez delivered a fiery speech telling De León: “You’re not welcome in these chambers.”

“I’m not OK with your presence on the floor today,” she said, “and I want Angelenos to know that I will be throwing my full support behind recall efforts.”

::

Those first few months, De León said in his interview with The Times, were “profoundly lonely.”

He talked about the men and women camped outside his house. He said his staff faced death threats. He called it “excruciatingly painful” to learn people “would actually believe that I would try to diminish their well-being or their power in our community.”

Asked if he considered resigning, De León said the thought did cross his mind. Instead, he stepped away from council meetings for two months, talking to constituents and focusing on the district.

“In many ways, what I learned was that there’s a lot of folks in Los Angeles who have huge, forgiving hearts,” he said.

An effort to recall Councilmember Kevin de León has fizzled. The organizer was unable to collect enough signatures to place the matter before voters.

In March, the De León recall drive fizzled out. By summer, only a handful of protesters were showing up to council meetings to demand his ouster.

Still, some community leaders remain convinced he should have left.

Michael Sweeney, president of the Eagle Rock Neighborhood Council and a self-described white liberal, said his organization stands behind a letter it sent calling on De León to resign. The group’s members also asked for their logo not to appear near De León’s name.

Sweeney said he’s heard from community members who remain skeptical about how contrite the council member has been.

“I can’t know whether he’s truly sorry or not. Nor can any of us,” Sweeney said. “But at the end of the day, it’s completely fair for people in the community to question whether the ways in which he has expressed, or not expressed, contrition or atonement, whether that makes him ... an effective representative.”

Despite those sentiments, De León showed he has retained a reservoir of support. Two weeks after launching his reelection campaign, he announced he had raised $118,000, with each donor spending no more than $900.

De León plans to run on what he says is a lengthy list of accomplishments: tens of millions of dollars for park improvements; state grants to install bike lanes, streetlights and hundreds of new trees; construction of “tiny home” villages that serve as temporary housing for the district’s homeless residents.

On top of that are the weekly food giveaways. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, De León’s office has distributed 30,000 boxes of food, many with stickers displaying his name and information about trash pickup, graffiti removal and pothole repairs.

De León’s name is also on the blue tote bags that are handed out, sometimes four at a time, and on the truck that delivers the groceries. At these events, residents say over and over again that De León deserves another chance, that he is a good person who made a mistake.

On a recent Thursday in Lincoln Heights, De León loaded a box with potatoes, ginger and bottles of Peet’s coffee into a small grocery cart pulled by Terry Harper, a neighborhood resident.

Harper, who is Black, said she was initially angry when she heard about the recording. As time passed, she concluded that he was “really remorseful.”

“He was fighting for his job. I like that,” the 60-year-old said. She paused and added: “But he shouldn’t do that again.”

Harper said she plans to vote for De León in March.

::

On L.A.’s Eastside, the audio had repercussions not just for De León’s district but for the political establishment that governs it.

Before the scandal, De León routinely held events with state and federal lawmakers who represented neighborhoods in his district — state Sen. Maria Elena Durazo, U.S. Rep. Jimmy Gomez, Assemblymembers Miguel Santiago and Carrillo. They all called for his resignation.

Santiago, one of the earliest supporters of De León’s unsuccessful 2022 run for Los Angeles mayor, said he telephoned him the day after the leak to inform De León he was publicly calling on him to step down. (De León disputed that, saying Santiago never told him he planned to call for his resignation.)

The conversation was brief, Santiago said, and didn’t end well.

“He was a friend before,” said the state lawmaker, who is also running to unseat De León in the March election. “We’re absolutely not friends now.”

Carrillo made her own call to De León last year, seeking to know “exactly what happened” during the recorded conversation. She said she never heard back.

Durazo, who had a longer and deeper relationship with the council member, also joined the chorus calling for his resignation. In a recent interview, she said De León should have finished his term and stayed out of the race.

“We need to give a fresh start to a new person, and just be able to move on,” Durazo said. “This community deserves that.”

::

By refusing to step down, De León forced his colleagues to continually reassess their strategies for interacting with him. Should they stay in the room when he enters? Even his toughest critics on the council quickly realized that if they walked out, they would lose the ability to pass new renter protections and homelessness initiatives.

Then the next question: Should they put their signatures on De León’s written proposals? That was eventually resolved as well, with more than half of his 14 colleagues deciding they would. By mid-September, dozens of De León motions had passed with little fanfare.

Then there was yet another dilemma: Should they avoid appearing with him in photographs, even when he was promoting a worthy cause? Hernandez, among De León’s most outspoken critics, answered that question in May, posing with him and other politicians at the unveiling of a crosswalk honoring the late Gloria Molina, the longtime county supervisor.

Months later, she told The Times she found those situations “difficult to navigate,” and made sure to stand as far from De León as possible. Hernandez said she doesn’t want to appear next to someone who “caused all this harm and really has not been accountable.”

Councilmember Hugo Soto-Martínez took the same approach last month while standing in front of the cameras at El Grito, a Mexican Independence Day celebration held outside City Hall. When his name was called, he made sure his colleague, Councilmember Imelda Padilla, stood between him and De León.

Soto-Martínez, in an interview, said he decided to attend the event even though he knew that meant appearing publicly with De León.

“It was the first [El Grito] since I was in office, and … I did not want to spoil that for the larger Latino community,” he said. “However, I did not want to be next to Kevin.”

Over the last year, council members repeatedly pointed out they had no legal authority to remove De León. Although they censured him, they acknowledged that such a move is largely symbolic.

Abdullah, with Black Lives Matter-L.A., criticized council members for allowing De León to conduct business. If the council won’t hold him accountable, she said, activists will take that step during the upcoming campaign.

“We’re going to make sure that we turn up the heat, not just on Kevin de León, but on anybody who decides to be in his orbit,” Abdullah said.

::

Five days after launching his reelection campaign, De León gathered with a group of Black attorneys to celebrate civil rights pioneer Willis O. Tyler, a lawyer who fought racially restrictive covenants in the early 20th century. After a brief countdown, the group unveiled a sign in De León’s district dedicating the intersection of 2nd and Spring streets as Willis O. Tyler Square.

De León, the lone politician at the event, spoke about staying committed to “the values of justice, equality and unity.”

“Even when we fall off track from our values and principles as a society, or even as individuals, heroes like Willis O. Tyler help redirect us, help center us, help put us back on the track to adhering to the values that make us stronger as a society and better individuals,” he said.

As De León spoke, someone yelled “bullshitter” from a passing car.

Attorney David Welch, whose law firm helped organize the event, said he didn’t speak to De León for about six months after the audio surfaced.

Welch, who is Black and lives in De León’s district, said he has seen the councilman work hard since then to regain the trust of the Black community — and all of his constituents.

“Knowing the council member, and knowing the work he’s promoted and where his heart is, it gave me an opportunity to forgive,” he said.

Others in attendance were more conflicted. Cannick — the political consultant, working on behalf of Welch’s firm — had helped plan the event with De León’s office. She said many other people, including judges, attorneys and elected officials, wanted to attend but did not because of De León’s presence.

That day, Cannick wore Louis Vuitton shoes and carried a Louis Vuitton purse, both purchased from a discount resale store — her subtle nod to the remarks in the recording about accessories and Bonin’s son. She kept her distance, stepping several feet back when De León approached. Cannick wanted to avoid being in any photos with him.

“Black people aren’t pleased with that man over there,” she said.

Hours later, Cannick struck a softer tone. In a post on Medium, she said someone who has been “an arrogant, racist jerk” still has the potential to be forgiven — but only if the offender makes amends and acknowledges wrongdoing. De León “has a long way to go before that happens with me,” she wrote.

Yet in her post, Cannick thanked him for holding the event, calling it “a start.”

Loyola Marymount University political science professor Fernando Guerra, who signed on to a letter in October 2022 calling for De León’s resignation, said he nevertheless believes the council member has a path to forgiveness with voters — and a shot at winning next year.

But if he makes his campaign about remorse and forgiveness, “he’s going to lose,” Guerra said.

Guerra said it makes “perfect sense” that De León, who is looking to protect not just his job but his legacy, would launch a campaign for another term.

“Had he resigned, it would have always been his epitaph, that he was in this scandal and he had to resign,” Guerra said. “Here he can say, ‘Hey, I never gave up.’”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.